Topics As Annotations¶

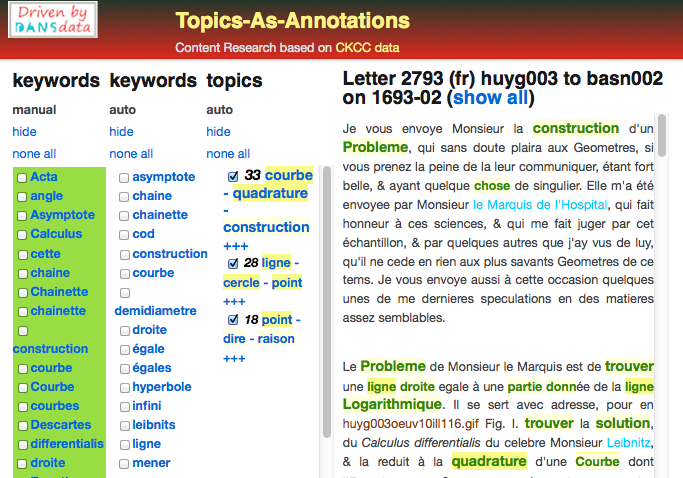

letter from Christiaan Huygens

Application¶

The application consists of two parts, a set of perl scripts for data conversion and a Web2Py web application for the end user.

Data conversion¶

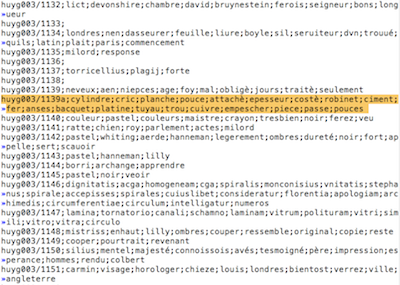

A number of Perl scripts to extract the data from the CKCC data. After that the output is transformed into several SQL files, to be bulk imported by an SQL database.

There is database, ckcc for the CKCC textual data, and there is a database, cannot, for the annotation data, which are topics and keywords.

Web Application¶

The Web Application is based on the web2py framework. The directory taa_1_0 contains the complete web app. It can be deployed on a web2py installation, but it will only work if it can connect to the relevant databases. Description ===========

Author: Dirk Roorda (References).

This is the motivation and explanation of the Topics/Keywords-As-Annotations (demo)-application (References). I am preparing a joint paper with Charles van den Heuvel (References) and Walter Ravenek (References) about the underlying idea. I am also working on a new idea: Portable Annotations (References) or: annotations that remain usable across variants of resources. Another example of the versatility of annotations as a carrier for the results of scholarship is Queries/Features as Annotations (References) demo application (QFA). Queries and their results are meaningful objects in the scholarly record, but how do we preserve them? We explore the idea to store queries on a corpus as annotations to that corpus. Contributors:

- Walter Ravenek (References), who delivered the data and annotations.

- Charles van den Heuvel (References).

- Eko Indarto (References)

- Vesa Åkerman (References)

- Paul Boon (References)

The TKA (References) demo app is a visualiser of topic annotations on a corpus of 3000+ letters by the 17th century Dutch scholar Christiaan Huygens.

The Case¶

Topic detection and modelling¶

Extracting topics from texts is as useful as it is challenging. Topics are semantic entities that may not have easily identifiable surface forms, so it is impossible to detect them by straightforward search. Topics live at an abstraction level that does not care about language differences, let alone spelling variations. On the other hand, if you have a corpus with thousands of letters in several historical languages, and you want to know what they are about without actually reading them all, a good topic assignment is a very valuable resource indeed.

There are several ways to tackle the problem of topic detection, and they vary in the dimensions of the quality of what is detected, the cost of detection, and the ratio between manual work an automatic work. Several of these methods have been (and are being) tried out in the Circulation of Knowledge Project a.k.a. CKCC* (References). See also a paper by Dirk Roorda (References), Charles van den Heuvel (References) en Erik-Jan Bos (References), delivered at the Digital Humanities Conference in 2010 (References) and a paper by Peter Wittek and Walter Ravenek (References) about the topic modeling methods that have been tried out (References).

Preserving (intermediate) results¶

manual keyword assignments

The purpose of the present article and demo is not to delve in topic detection methods. Our perspective is: how can we gather the results of work done and make it reusable for new attempts at topic modelling and detection? Or for other ways to uncover the semantic contents of the corpora involved?

At this moment, CKCC (References) has not obtained fully satisfactory results in topic modelling. But there are:

- results in automatic keyword assignments,

- manual assignments of topics in a subset of the corpus

- automatic topic detection on the basis of the LDA algorithm

The outcomes of this work are typically stored in databases, or bunches of files of type text or csv. They involve internal identifiers for the letters. They cannot be readily visualised.

I propose to save this work as annotations, targeting the corpus.

The interface¶

TKA (References) is a simple demonstration of what can be done if you store keyword and topic assignments as annotations. Here is an overview of the limited features of this interface. Bear in mind that very different interfaces can be built along the lines of this sources-with-annotations paradigm.

This interface is designed to show the basic information contained in the letters and the keyword/topic aasignments.

The columns¶

The rightmost column is either the text of a selected letter, or a list of letters satisfying a criterion.

The other three columns are the keywords and topics that are associated with the displayed letter, or with any of the letters occurring in the list on the right.

The source¶

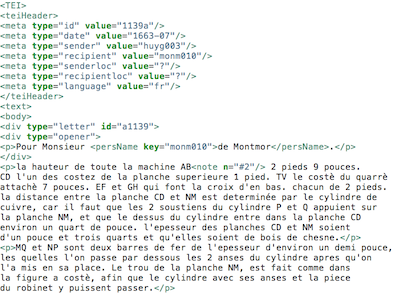

The source is the complete correspondence of Christiaan Huygens, which are predominantly letters in French, but there are also a few Dutch letters. The texts derive from TEI-marked-up texts as used by the CKCC project (References).

Keywords and Topics¶

There are two kind of keywords. In the left most column you see the manually assigned keywords. If you hover over the space to the right of them with the mouse pointer, you see the author of the assignment. If you click on them, you will get a list of all letters that have that keyword manually assigned to them.

In the middle column you see the automatically detected keywords (only if you have selected a single letter or a subset of letters).

In the right column you find the topics. These topics are the result of an automatic attempt at topic detection. A topic is a collection of words, which together span a semantic field. Which field is often hard to infer, and quite often there does not seem to be a common denominator at all. The words of a topic all have a relative weight with which they contribute to that topic. This weight shows up as a number between 1 and 100, to be interpreted as a percentage.

The topics are represented by means of its three most heavily contributing words. If you want to see all contributng words, click on the +++ following the words.

Topics have been assigned to letters with a certain confidence. This confidence is visible in the single letter view: it is the number between 1 and 100 before the three words.

Weights and confidence have different scales in the database than on the interface: I have used calibration to a scale from 1 to 100 and rounding for readability purposes.

You can highlight keywords and topics in the text, selectively.

The Idea¶

The main idea is to package the outcomes of digital scholarship into sets of annotations on the sources. Our model for annotations is that of the Open Annotation Collaboration (References): a topic has one body and one or more targets. Metadata can be linked to annotations.

Keywords as Annotations¶

In the present case, keywords and topics are targeted to letters as a whole. So the granularity of the target space is really coarse.

For keywords, the modeling as annotation turned out to be a straightforward matter. A keyword assignment by an expert or algorithm corresponds to one annotation with the keyword itself as body, and the letters to which that keyword is assigned as the (multiple) targets. The author of the assignment is added as metadata.

Topics as Annotations¶

The mapping from topics to annotations is not so straightforward. Several alternative ways of modelling are perfectly possible. The complication here is the confidence factor with which a topic is assigned to a letter. This really asks for a three way relationship between topics, letters and numbers, but the OAC (References) model does not cater for that. We could work around them by adding relationships to our annotation model, but that would defeat the purpose of the whole enterprise: packaging scholarship into annotations to make them more portable. So we want to stick to the OAC (References) model.

Here is a list of remaining options.

Confidence as metadata¶

Topic is body, letters are targets. The confidence is an extra metadata field.

Technically, this is a very sound solution, because the confidence really is a property of the assignment relation.

But the confidence is the outcome of an algorithm and as such a piece of the data. Treating it as metadata will cause severe surprises in processing chains that treat metadata very differently from data.

Topics as target¶

Confidence is body, topic is target, letters are other targets.

Technically, this is doable. But it is fairly complex and it asks for a rather complex interpretation of the targets: in order to read the topic off an annotation, one has to find the one target of it that points to a topic.

With respect to interpretation: under the standard interpreation of annotations we would read that the confidence is what the annotation says about a topic and a set of letters. This is odd, especially when the bodies of keyword annotations do contain the keywords themselves. This makes it much harder for interfaces to show topics and keywords in their continuity.

Confidence as target¶

Topic is body, confidence is target, letters are other targets.

Technically this is no different than the previous case.

The interpretation is even more odd than in the previous case, since the target is a single number. As if we really have web resources around that only contain one number. Not natural.

Combine topic and confidence into the body¶

This is the option chosen for the demonstrator.

The body is structured, it contains a topic and a confidence, only letters are targets.

The only technical complication is the structured body.

The interpretation is just right: an annotation asserts that this topic - confidence combination applies to this set of letters.

There is another price to pay: we cannot subsume all letters that are assigned a specific topic as the targets of a single annotation. Every letter - assigned topic combination requires a separate annotation, because of the distinct confidence numbers. Any interface that wants to present the letters for a given topic will have to dig into the structure of the annotation bodies. This limits the genericity of the approach.

Express confidence in an annotation on an annotation¶

Topic is body of annotation1, letters are targets of annotation1, confidence is body of annotation2, annotation1 is target of annotation2.

Technically, it is more complicated to retrieve these layered topic assignment annotations, it is a cascade of inner joins. But it is doable.

The interpretation is completely sound. Annotations on annotations is intended usage, and the confidence is really a property of the basic topic assignment.

The Work¶

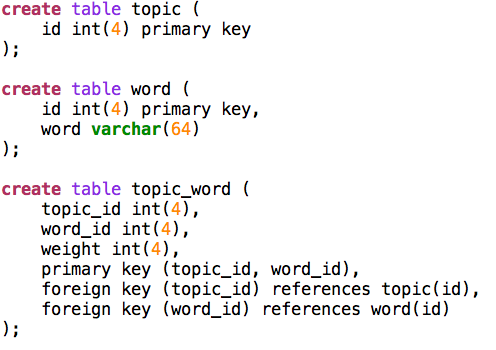

Annotations in Relational Databases¶

Here I discuss how the annotations have been modelled as relational databases.

Indeed, these annotations have not been coded into RDF, they have no URIs, so they do not conform to OAC (References). Instead, they have been modeled into relational database tables.

There are several reasons for this:

# the annotations should not be tied to specific incarnations of the sources # the annotations are to drive interfaces in different ways, depending on what it is that is being annotated

The main reason for 1. is that those sources are not yet publicly online, or if they are, they have not yet stable uris by means of which they can be addressed.

Because of 2. we need random access to the annotations with high performance. The easiest way to achieve that is to have them ready in a relational database.

Nevertheless, there is a sense in which we conform to OAC (References): the annotations reside in a different database than the sources do, and the link between annotations and targets is a symbolic one, not checked by the database as foreign keys. So the addressing of targets is very flexible.

This establishes modularity between sources and annotations, and the intended workflow to deal with real OpenAnnotations (References) is:

# if you encounter a set of interesting rdf annotations on a source that you have in your repository: import the rdf annotations into a relational database, and translate target identifiers into database identifiers; # if you want to export your own set of annotations to the Linked Data web: export the database annotations to a webserver, translating target identifiers to URIs pointing to your sources.

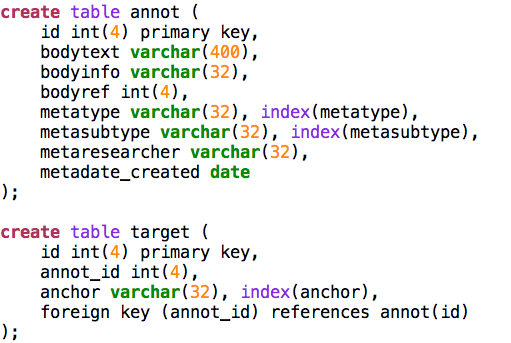

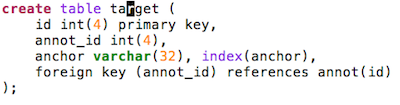

Data model for annotations¶

The datamodel for annotations containing topics and keywords is as straightforward as possible. Some observations:

#There are separate databases for topics, which act as bodies of the annotations, and for the annotations themselves. #Topics are symbolically linked to the annotation database, not by database-enforced foreign keys. #Topics do not have external ids, so the annotations link to them by means of their database id. This is a challenge if you need to export topics as web resources. #Bodies have structure: there are three fields: ##**bodytext** for bodies that are ordinary text strings, like keywords; ##**bodyref** for bodies that are database objects themselves; this field is meant to contain the id of the body object; the application is meant to ‘know’ in which table these objects are stored; ##**bodyinfo** additional information inside the body; here we use it for storing the confidence factor, which is a floating point number stored as a sequence of characters; ##there is no sharing of targets between annotations, the database model admits only one annotation per target. If we allowed target sharing, we would need an extra cross table between annot and target, which would burden all queries with a lot more inner joins. Whether efficiency suffers from or improves by this choice I have not investigated. In QFA (References) I have used target sharing, and it worked quite well in a corpus with nearly 500 000 targets. Especially the targets of the features there would have caused the target table to explode of sharing were not used. #The letters, which are the sources that are targeted by the annotations, are in a separate database as well. They carry ids given with the corpus. These are the ids that are used as the symbolic targets in the target table of the annotations. #There is no split between the annotations and their metadata. The reason for the latter integration is that the annotation machinery should have a decent performance. Most queries sift through annotations by metadata, so for this demo I chose a simple solution.

The main intention between these choices is to keep the interface between the annotation model and the real world objects that constitute the bodies and the targets, as free as possible from database-specific constraints. We want to use the model for more than one kind of annotation!

Data Statistics¶

Since performance is an important consideration, here are some statistics of the sources and annotations of TKA (References).

| quantity | amount | extra info |

|---|---|---|

| Number of letters (in the Christiaan Huygens corpus) | 3090 | 13MB |

| Number of topics | 200 | 100 french, 100 dutch |

| Number of words in topics | 2202 | |

| Total number of annotations (keyword manual, keyword auto, topic | 18884 | |

| Total number of targets | 37468 | |

| Keyword (manual) annotations | 801 | |

| Keyword (manual) targets | 859 | |

| Keyword (auto) annotations | 11721 | |

| Keyword (auto) targets | 29547 | |

| Topic annotations | 6362 | |

| Topic targets | 7062 |

Lessons Learned¶

Not all annotations are equal¶

The annotation model is very generic, and many types of annotation fit into it. Here we saw several kinds of keywords and topics, each with different glitches. In the QFA (References) demo there are linguistic features as annotations and queries as annotations, which require completely different renderings.

So the question arises: what is the benefit of the single annotation model if real world applications treat the annotations so differently?

And: how can you design applications in such a way that they benefit optimally from the generic annotation model? Now that we have interfaces for at least three real world type annotations we are in a position to have a closer look, and to gather the lessons learned.

The benefits of a unified model¶

A basic interface for annotation¶

Interfaces come and go with the waves of fashion in ICT. Most of them will not be sustainable in the long term. If the interface draws from data that is modeled to cater for the needs of the interface, it will be hard to re-use that data when the interface has gone. Moreover, even will the intended interface still exists, it is better if the data can be used in other, unintended applications. If the data conforms to the annotation model, there is at least a generic way to discover, filter and render annotations. This is very good if you are interested in the portability of the scholarly work that is represented in annotations.

Anchors for annotations¶

Annotations point to the resources they comment on. OAC (References) even requires that this pointing is done in the Linked Data way: by proper http uris. If those resources are stable, maintained by strong maintainers such as libraries and archives and cultural heritage institutions, it becomes possible to harvest many sorts of annotations around the same sources. This is an organizing principle that is quite new and from which a huge benefits for datamining and visualisation are to be expected.

However, this is only interesting if the uris leading to the resources are stable, and if it is possible to address fragments of the resources as well. To the degree that we have stable anchors for fragments, the OAC (References) targeting approach is nearly ideal.

Absolute addressing versus relative addressing

In real life there are several scenarios where there is no stable addressing of (fragments) of resources. This happens when resources go off-line into an archive. If we want to restore those resources later on, the means of addressing them from the outside may have changed. Moreover, there might not be a unique, canonical restored incarnation of that resource. How can one use old, archived annotations for this resource?

The solution adopted in QFA (References) and here in TKA (References) is to work with localized addresses. These are essentially relative addresses that point to (fragments) of local resources that are part of a local corpus.

There is a FRBR (References) consideration involved here. FRBR (References) makes a distinction between work, expression, manifestion and item. Work is a distinct intellectual or artistic creation. As such it is a non-physical entity. Expression, manifestation and item point to increasing levels of concreteness: an item is an object in the physical world. Wikipedia illustrates these four concepts with an example from music:

| FRBR (References) concept | example | keyword |

|---|---|---|

| work | Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony | distinct creation |

| expression | musical score | specific form |

| manifestation | recording by the London Philharmonic in 1996 | physical embodiment |

| item | record disk | concrete entity |

The full refinement of these four FRBR (References) concepts is probably not needed for our purposes. Yet a distinction between the work, which exists in an ideal, conceptual domain, and the incarnations of it, which exist in a lower, more physical layer of reality, is too important to ignore. It is important for the ways by which we keep identifiers to works and incarnations stable. Identifiers to works identify within conceptual domains, they have no function to physically locate works. These identifiers are naturally free of those ingredients that make a typical hyperlink such a flaky thing. So whenever annotations are about aspects of a resource that are at the work-level, they have better to target those resources by means of work-identifiers. By the way, the distinction work-incarnation also applies to fragments of works. Most subdivisions, like volumes, chapters and verses in resources do exist at the work level. Of course, there are some fragments that are typically products of the incarnation level, such as page.

Portable Annotations

How does this discussion bear on our concrete demo application?

Suppose we have a set of annotations to some well-identified letters in the Christiaan Huygens corpus. These annotations may also be relevant to the same letters in another incarnation of that Christiaan Huygens corpus. This other incarnation might be a another text encoding or even a different media representation or even another version with real content differences. With well-chosen, relative addresses, it is possible to make the targeting of annotations more robust against such variations.

Then a package of annotations on the Christiaan Huygens letters, made in the initial stages of the CKCC project (References), can be stored in an archive. Later, it can be unpacked and applied to new incarnations of those letters. If other research groups have curated those letters, chances are good that this annotation package can also be applied to those versions.

This all works best if the sources themselves and their fragments have work-level identifiers that are recognized by whoever is involved with them. Even if this is not the case, it is easier to translate between rival identifier schemes at the work level, than to maintain stable identifiers at the incarnation level.

There are no mathematically defined boundaries between works and incarnations. Even FRBR (References) leaves much to the interpretation. With a bit of imagination it is easy to define even more FRBR (References)-like layers in some applications. And then there is the matter of versioning. To what extent are differing versions incarnations of the same work? This is really a complex issue, and I plan to devote a completely new chapter plus demo application to it. See Portable Annotations (References).

Metadata and Annotations¶

The OAC (References) model defines an annotation as something that is a resource in itself. That means that annotations can be the targets of other annotations (and probably of itself as well, but I do not see a use case for that right now), and that annotations can be linked to metadata. So metadata is not part of the OAC (References) model, but the fact that metadata on annotations is around, is well accomodated.

With metadata the divergence sets in. Concrete applications need metadata to filter annotations, but there is no predetermined model for that metadata. So here is a point where applications become sensitive to the specifics of the information around annotations. Or, alternatively, applications might discover the metadata of annotations, and make educated guesses as to the filtering of the annotations they want to display. Very likely this will so computation intensive, that a preprocessing stage is needed, in which the metadata that is around will be in fact indexed according to an application specific metadata model.

metadata fields in Queries/Features As Annotations

metadata fields in Topics As Annotations

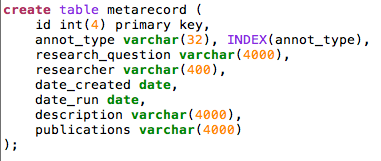

Let me conclude with an account of the metadata that the TKA (References) and QFA (References) demos needed to function. See the screenshots on the right.

Type and Subtype

One of the most important characteristics is the type of the annotation.

In QFA (References) it tells whether the annotation expresses a (linguistic) feature, or a query and its results. As features and queries are displayed differently, it is important to be able to select on type and subtype, and to do it fast (that’s why there is an index on these columns).

In TKA (References) there is a field metatype which is used to distinguish between keywords and topics, and a field metasubtype which distinguishes between manual annotations and automatic annotations, i.e. the results of algorithms.

Provenance

In a world where annotations are universal carriers for scholarship, provenance metadata is of paramount importance. Without it, it would be very difficult to assess the relevance and quality of the annotations that one discovers around a resource. For QFA (References) there are, even in demo setting, a handful of fields: researcher, research question, date_created, date_run, publications.

A typical use case for QFA (References) is this: a researcher in the future comes across some targets of a query annotation by way of serendipity. He navigates to the body of the annotation, which is a query instruction. Very likely he has no means at hand to run that query, but he can look up the other query results. Apart from that he is able to see why this query has been designed, which question it answers, and who has done it and when, and to which publications this has lead. Using this information he can find related research questions, queries and results. In this way a quite comprehensive picture op past and ongoing scholarship around these sources can be obtained, without maintaining the engines that once run all those queries.

Among the possible use cases for TKA (References) is this one: in order to get algorithmic access to the semantics of all those tens of thousands of 17th century letters various methods are tried to get keywords and topics. Some methods yield keywords in purely automatic ways. Other methods require training by manual topic assignments by experts. The methods must be tested against test data. Parameters will be tweaked, outcomes must be compared. Precision and recall statistics indicate the success of those methods. Yet something is missing: a view on all those keyword/topic assignments in context, where you can switch on and off different runs of the algorithms, and where you can assess the usefulness of the assigned labels and hit on the obvious mistakes.

If all topic/keyword assignments are expressed as annotations, than it is the provenance metadata that enables the application to selectively display interesting sets of annotations.

Even more importantly, there is real gold among those annotations, especially the manual ones by experts. They can be used by other projects in subsequent attempts to wrestle semantic information from the data. Good provenance information combined with real portability of annotations will increase the usefulness of those expert hours of manual tagging.

Real applications driven by annotations¶

How do real applications utilize the common aspects of the annotation model, and how do they accomodate the very different roles that different kinds of annotations play in the user interface? Let me share the experience of designing demo applications driven by annotations.

Approach¶

First a few general remarks as to the approach we have chosen.

#we wanted a broad range of annotations, in order to explore how fit annotations are to express the products of digital scholarship. That is why we considered queries, features, keywords and topics all as annotations; #rather than using OAC (References) annotations with real uris, we modeled annotations directly in relational databases. We see OAC (References) more as an interchange format, handy for exporting and publishing annotations and importing them into other applications; #we took care to separate the sources from the annotations: they are stored in different databases. We think that sources and annotations should be modular with respect to each other: one should be able to add new packages of annotations to an application; one should be able to port a set of annotations from one source to another incarnation of the same work (in the FRBR (References) sense); #even when we stretched the use of annotations to possibly unintended cases such as queries, we took care that the information we stored in body, target and metadata can be naturally interpreted accordingly; #we have not built any facility to create or modify annotations, nor sources for that matter. The motivation for these demos come from archiving, where modifying resources is not an important use case.

Structure¶

The common denominator of these annotation rendering demo applications is that they let the user navigate to pieces of the source materials. The application retrieves the relevant annotations, and gives the user some control to filter and highlight them. In the case of QFA (References) the query results are not fetched before rendering the page, but only on demand of the user, by means of an AJAX call. The feature results are fetched immediately, together with the sources.

Differences¶

The differences are there where the abstract annotation model hits the reality of the use cases: the contents of the bodies, the addressing of the targets, the modeling of the metadata. Also the visualisation of the annotations differs.

Bodies

Bodies tend to have structure. A choice must be made whether to express that stucture in plain text, or to use database modeling for it. Before discussing this choice, let me list what the bodies look like in each case.

| Kind of annotation | form of body | interpretation of annotation |

|---|---|---|

| Query | plain text: statement in a query language | targets are results of query |

| Feature | plain text of the form: key*=*value | targets are source fragments for which the feature key carries the value |

| Keyword | plain text of the form: keywordstring | targets are letters in which keywordstring occurs |

| Topic |

|

targets are letters to which the identified topic applies with a confidence factor |

| Topic |

|

targets are letters to which the identified topic applies with a confidence factor |

Remember that topics are collections of words, where each word has a certain relative weight in that topic. This asks for plain old database modeling.

There are conflicting interests here. In our annotation model we want to accomodate annotations in their full generality. Yet the application will specialize itself around a few annotation types that are known beforehand. If the application does not specialize, its performance will not be up to the task. Yet we have tried to keep the structure of a body as generic as possible. The features case, for example, is a plain text body, but there is in fact the additional structure of keys and values.

But the topics case really would be awkward if we had to spell out the complete topic information for each annotation with that topic in the body. So we decided to give each body three content fields:

- bodytext for plain text content

- bodyref to contain an identifier pointing to an object in a(nother) database, without foreign key checking

- bodyinfo a bit of extra info of the body on which the application may search

By abstaining from database constraints for bodyref we keep the model still very versatile. If the application knows the database to look in, the body object can be found. Hence annotations with bodies that refer to arbitrary databases and tables can be accomodated without changes to the database model.

By having an extra bodyinfo field of type string, we can separate body information in two fields on which the application can efficiently perform filter operations. In the case of topics, the bodyinfo stores the confidence number. If topic bodies had been stored as plain text including this number, it would have been very inefficient to select topics regardless of this confidence number.

Probably the best option, but one that we have not implemented, is: express the confidence as body of a new annotation that targets the absolute topic assignment annotation.

The OAC (References) model is really concise, and there are many ways to link to additional data, which results in quite of few options to pursue when one maps topics onto annotations.

Targets

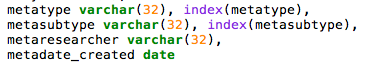

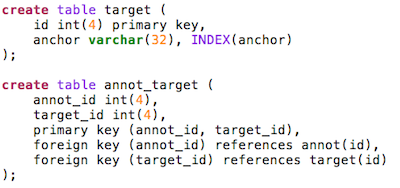

target model for queries/features

target model for keywords/topics

Targets are resources or fragments of resources. As there is no standard way to refer to fragments of resources, we decided to always use a string to denote a target. This is the field anchor, of type string. We do not fill this field with database identifiers, but with identifiers that come from the sources themselves.

As an illustration: before version 3.0 of QFA (References) we used the absolute word number of a word occurrence.

The first word of the Old Testament got number 1, and the last word number 430156.

Now the first word gets anchor gen_001:001^001 and the last word gets anchor ch2_036:023^038.

These anchors refer to books, chapters and verses and specify a word in a verse by their order number in that verse.

The last word of the bible is the 38th word of the 23th chapter of the second book of Chronicles.

In TKA (References) only letters as a whole are anchored.

For example, the letter of the example screenshot above has identifier 1139a,

which is clearly not a database identifier.

An obvious difference between the target model for queries/features on the one hand and keywords/topics

on the other hand is that the former allow target sharing between annotations.

This is only a pragmatic issue with no semantic consequences and not too much performance impact.

The model without target sharing is definitely simpler, and fewer inner joins are needed to get from target to body, for instance.

The model with target sharing does not enforce it.

Even if targets are shared, there is the need for a record in the cross table annot_target per target per annotation.

So this will only gain something if the anchor field requires a significant amount of text per anchor.

Metadata

In fact, we have very little metadata, most of it unstructured. So we can afford to store it in a separate table (in the queries/features case) or even in extra fields in the annotation record itself. As soon as the relevant metadata becomes more complex, it is better to separate it thoroughly from the annotations, and make the connection purely symbolic, like we did with the connection between target anchors and the targets themselves.

Visualisation

Each type of annotation asked for different visualisations on the interface. The common aspect is that targets are highlighted, and bodies are displayed in separate columns, one for each (sub)type of annotation. The differences between queries and features and topics and keywords are: #for queries only those bodies are shown that have targets in the rendered part of the source; whereas for features all features/value pairs are selectable, regardless of their occurrence in the displayed passage of the source; #query targets are highlighted whereas features targets are highlighted according to display characteristics under user control; #queries and features have targets at the word level whereas keywords and topics are targeted at the letter level, but the individual occurrences are highlighted by means of a generic javascript search in element content, which is less precise!

Implementation¶

In order to rapidly implement our ideas concerning annotations and sources we needed a simple but effective framework on which we could build data-driven web applications. Web2py (References) offers exactly that.

We needed very little code on top of the framework, a few hundred lines of python and javascript. Deployment of apps is completely web-based, and takes only seconds.

Most work went into the data preparation stage, where I compiled data from various origins into sql dumps for sources and annotations. This was done by a few perl and shell scripts, each a few hundred lines again.